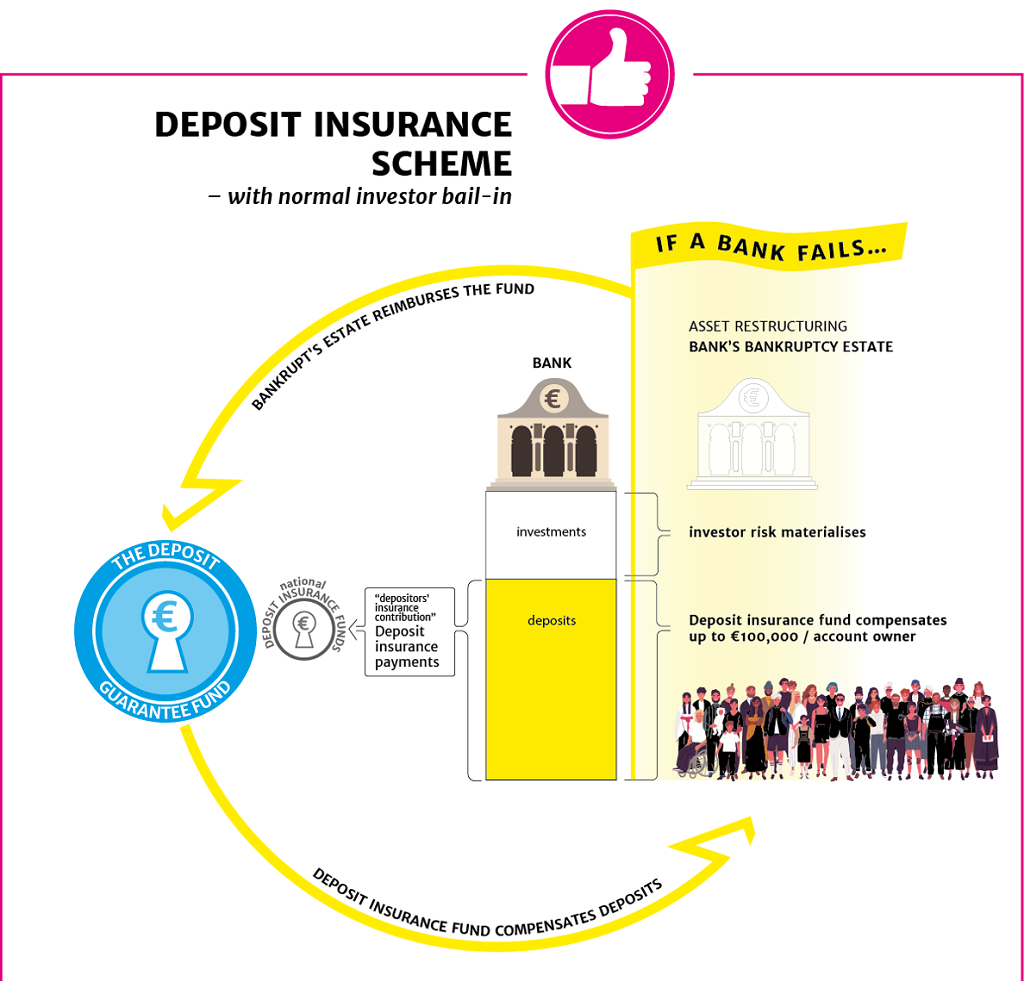

- When a bank is failing or likely to fail, the losses should be borne by the bank’s investors.

- It is not responsible to shift the losses onto taxpayers: investor liability is fundamental to investment.

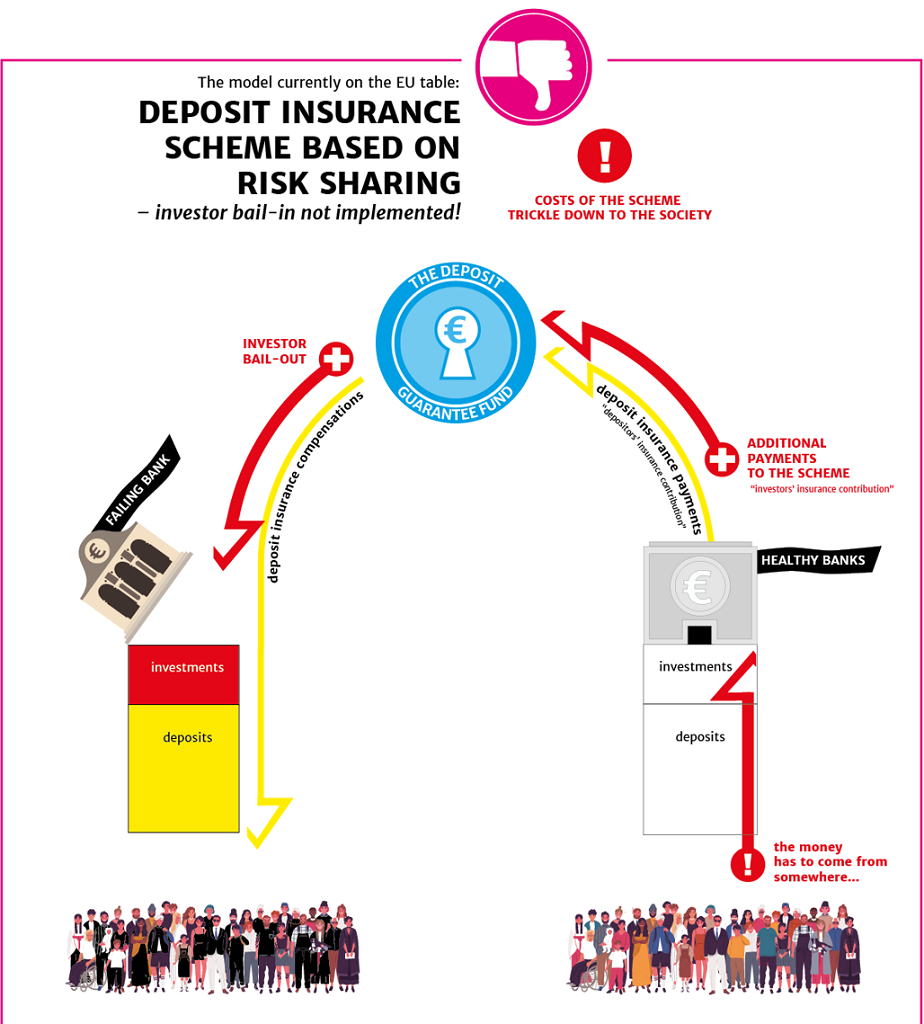

- Finance Finland is surprised at the Commission’s plans, which pave the way for the establishment of a European deposit insurance scheme as the Banking Union’s third pillar without respecting the principle of bail-in.

On 18 April, the European Commission adopted an extensive legislative proposal on bank recovery and resolution, which would utilise national deposit guarantee schemes as a source of funding. According to the proposal, this is a staging post on the road to a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS).

The EDIS has been a long-term goal especially for many Southern European member states and EU authorities, who hold that banks’ losses should not be borne by the banks’ investors alone but also by other parties. This would include national deposit guarantee schemes.

“This is entirely against the idea of bail-in, one of the fundamental EU principles. If the EDIS is established without a working recovery and resolution framework, banks’ retail customers might have to take part in covering a failing bank’s losses. Is this what we really want?” asks Finance Finland’s Head of Banking Regulation Olli Salmi.

Effective regulation for struggling banks

The Finnish financial sector has designed and also submitted to the Commission an alternative model to implement a common deposit guarantee scheme, should one become necessary.

“It is not in line with the fundamental rights of the EU or Finland to have others foot the bill for one economic unit’s losses either directly or indirectly”, Salmi points out.

Working bank recovery and resolution regulation is a prerequisite for a functioning deposit guarantee scheme. The Commission’s latest proposal addresses this need only partially. Although the positive flipside is that the scheme could be used to facilitate structural reorganisations, such as moving deposits from an ailing bank to a healthy one, the proposal nevertheless includes several potentially problematic elements, such as extending the scope of the deposit guarantee too far beyond the deposits of private individuals. This could enable and lead to the use of taxpayers’ money with the deposit guarantee fund and banks only acting as intermediaries.

“These problematic elements could even result in critical defects in the system – especially if a single European scheme is eventually adopted”, Salmi says.

According to the proposal, member states’ powers to save banks using public funds are to be restricted. While this is a step in the right direction as such, it is also a double-edged sword: public funds could be used to organise an orderly market exit for a failing bank without taking on losses. This is sensible use of public funds– but its success depends on correctly timed action by the (national) resolution authorities.

“If the deposit guarantee scheme were to cover a bank’s losses, it would carry the risk that the authorities of some member states might take inappropriate action when a bank is failing or likely to fail. To prevent moral hazard, it would only be natural for the member state to bear the losses caused by its own authorities”, Salmi concludes.

Still have questions?

|Contact our experts

Looking for more?

Other articles on the topic

National liability must come before liquidity assistance – Finance Finland’s summer party panel focused on the European deposit insurance scheme

Banking Union’s Single Resolution Fund reached its target level – the criteria for accessing the fund must be kept strict

The Government and the Commerce Committee adopted a constructive stance on furthering the Banking Union – investor bail-in must not be scrapped

As deposit guarantee and bank resolution are being developed, bail-in must not be forgotten